Increasing capacity and meeting decarbonisation goals – can it be done?

We discuss the cost and infrastructure considerations of switching to an all-electric fleet of off-highway vehicles.

Justin Benson is a Partner and Dominic Tribe is a director at Vendigital. They are both automotive sector specifically and recently shared their insights with E&T.

UK car makers will have to address some crucial challenges around battery production if they’re going to survive in an age of electric vehicles.

Nissan’s announcement that it is going ahead with plans to develop a £1bn battery gigafactory in Sunderland has been widely welcomed as a step in the right direction. Despite the enormous scale of the plant, it will still leave the UK with a significant shortfall in battery production capacity – can Britain’s car industry survive?

The survival of the UK’s automotive industry rests on three key factors – investment in more gigafactories, investment in innovation and the ability to scale production in line with growing EV demand.

Having recognised the importance of adding battery production capacity and creating a local ecosystem of suppliers, the UK government is already in talks with a number of car manufacturers over plans to invest in several more gigafactories. Plans for a further facility at Blyth, Northumberland, are reported to be progressing well and have the backing of UK-based battery manufacturer Britishvolt. In addition, plans were submitted by Coventry City Council in July for a new gigafactory at Coventry Airport, close to the UK Battery Industrialisation Centre. A number of other potential projects are under discussion.

To remain competitive, UK-based car makers need access to a domestic supply of battery packs in the future, if only to avoid the significant costs associated with transporting these bulky components from Asia. For car makers planning to export EVs to the 27-nation EU in the future, the ability to demonstrate that 70 per cent of the value of a car battery, and indeed the car itself, comes from Britain or inside the EU, will be critical from 2027 onwards. This is when new, stringent ‘rules of origin’ take effect.

The SMMT has forecast that the UK will have 12GWh of lithium-ion battery capacity by 2025. However, considering that it takes about 9GWh of capacity to create around 100,000 EVs, and UK EV sales reached 108,205 last year, it is clear that this is nowhere near enough. To put the shortfall into perspective, by 2025, the lithium-ion battery capacity of other Western countries, such as Germany and the US, is expected to have reached 164GWh and 91GWh respectively.

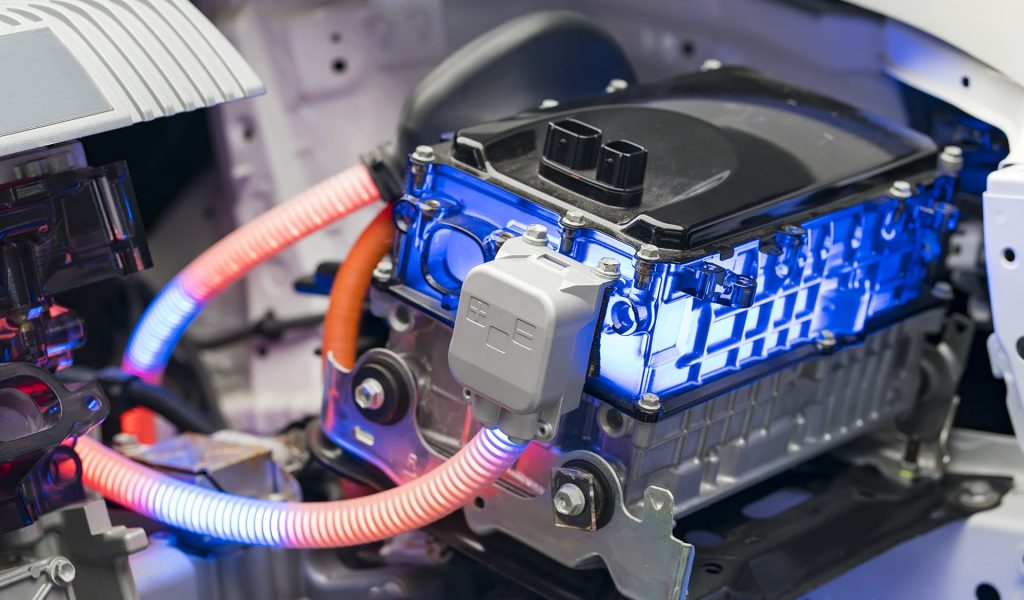

In addition to stepping up investment in gigafactory production, more investment in battery innovation is urgently needed. The manufacture of lithium-ion batteries is reliant on supplies of rare-earth metals, including lithium and cobalt, both of which are finite resources and can only be sourced from certain countries. Investing in the development of alternative technologies, such as solid-state or lithium-sulphur batteries, could deliver vital safety and efficiency benefits, and other chemistries involving the use of zinc and sodium sulphur are also being explored. Some scientists have turned their attention to lithium extraction from seawater and a recently published study has shown that there is an estimated 230 billion tonnes of lithium in the ocean. Investing in innovation activity now could deliver a competitive advantage in the future.

The third factor that could determine whether Britain’s car industry survives or not is the ability to scale battery production in line with growing EV demand. This is actually not as easy as it sounds and will require a careful focus on supply chain management. Scaling up production will always bring economies of scale and the same is true for gigafactory manufacturers. They will find that, as they increase production, it becomes easier to strike competitive deals with raw material suppliers and secure their source of supply. However, scaling too quickly brings risks of course. If they increase capacity too quickly, they could be left with excess inventory, which carries a cost implication. Alternatively, they could miss out on orders simply because they can’t deliver the volumes required without bringing on a new production line, which could take several months.

For EV makers, the stakes have reached new heights. There is a need to press ahead with investment in gigafactory battery production in order to supply their own mainstream EV production lines, while continuing to sponsor innovation by working with tech partners to explore substitutes for lithium-ion batteries. Gigafactory manufacturers will also need to ensure that when the time comes, they pace their ramp-up just right.

Sign up to get the latest insights from Vendigital

Get in touch

Related Insights

We discuss the cost and infrastructure considerations of switching to an all-electric fleet of off-highway vehicles.

EV makers in the UK and Europe are warning that Zero Emission Mandates are simply not doable and subdued levels of demand could force them to close factories. Should the industry embrace Chinese capability before it’s too late?

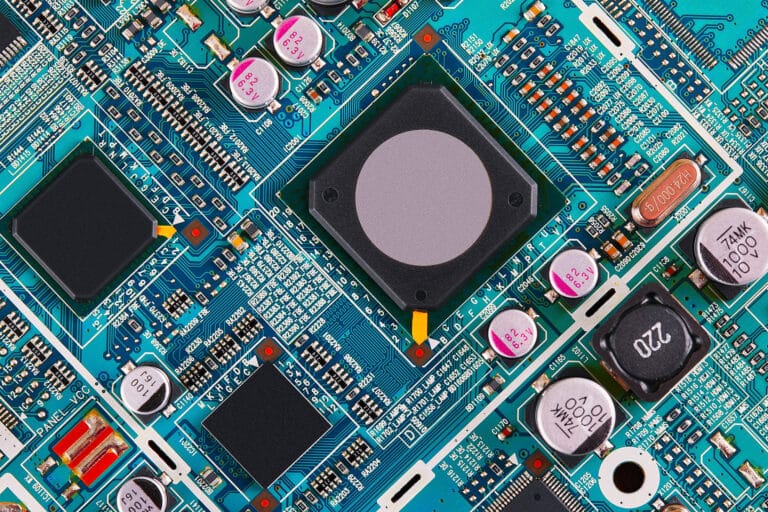

In our latest report we examine the impact of power electronics and the importance of inverters in EV manufacturing.

Subscribe to our newsletter