Increasing capacity and meeting decarbonisation goals – can it be done?

We discuss the cost and infrastructure considerations of switching to an all-electric fleet of off-highway vehicles.

It is well known that the whole automotive industry is engaged in a pivot towards Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs). This shift requires the whole industry at all tiers and levels to adjust technology, skills, established relationships and ways of working, with many of these changes being incredibly difficult to execute. Supply chain design is a crucial element in achieving the required pivot.

Shifting demands currently met by traditional responses

Whilst the new entrants and start-ups have something of an advantage through not having “baggage” by way of culture, many still rely on recruits from established industry players who bring their processes and expectations of how things operate. These expectations include areas such as:

All of these areas – and the need for new thinking with regard to them – are brought into focus by the novelty of BEV development and the current maturity (or lack of it) within the industry. For example, whilst the “skateboard” seems to be the default approach to platform design, some voices in the industry are pointing out that having significant amounts of mass at the vehicle extremities is not best for vehicle dynamics or even vehicle safety. This type of thinking could lead to different solutions being developed with differentiation being a potential benefit. Some brands might want to place occupants closer to the floor than skateboard architecture allows, whist others might be happy to employ “in wheel” motors for packaging and other efficiency reasons. Others again might look to centralise mass in order to get low polar moments of inertia so as to benefit handling.

Green shoots in supply chain innovation are emerging

Given the above, it is clear that we are seeing a new industry emerge and in many ways there are parallels with the auto industry as it developed through the early decades of the last century. Then, as now, new solutions emerged which took the horseless carriage from being exactly that to a new place: the automobile, with new designs and innovative solutions to the problems of mass transportation. I suspect that we will eventually see the same thing with BEVs both in terms of the product itself and the methods of manufacture.

Some specific changes that seem to be moving in that direction are:

Picking up on some of these points, it has become clear that “old” approaches when applied to EVs lead to sub-optimal performance both at the product and supply chain levels. For example, if engineers design a powertrain “system” as an integrated set of modules and components, then it has to be procured with that thinking in mind. If the approach becomes “buy the bits at the lowest cost” then system performance will be jeopardised and overall vehicle appeal put at risk.

In some cases, suppliers are required to play a significant role in developing new products and technologies and this is often underpinned by some sort of commercial agreement. It is important in such cases for both sides to be clear in their responsibilities and how they get value for money out of the commercial agreement. We have seen a number of cases where arrangements such as these have led to difficult situations as new vehicles are being brought to market.

The traditional supplier base is also changing. There are many new suppliers around the world but especially in South East Asia, with new capabilities that are specifically beneficial to BEV manufacturers and their first-tier suppliers. In many cases, they have new manufacturing technologies and/or product IP that can significantly reduce BOM cost and in some cases enhance product competitiveness. On the flip side, however, many of these suppliers are hard to identify and might not respond well to the traditional RFQ approach. They therefore need to be found, qualified and nurtured in order to get the best outcome for all parties.

Similarly, if micro-factories are determined as the appropriate manufacturing approach, design has to be matched to the demands and constraints of the downstream infrastructure. High cost Body in White (BIW) facilities are no longer an option in this scenario and the alternatives, which usually entail composite panels with joints bonded in some way, have their own issues in terms of strength, NVH (Noise, Vibration and Harshness) and integrity/leak prevention. Mitigating all of this has to be tackled cross functionally in a significant and meaningful way – and, essentially, include procurement and supply chain specialists.

Conclusion

So, the new world of BEV design and manufacturing as well as being exciting and dynamic has many challenges. The industry is learning quickly but it must be even more ready to adapt and be open to new approaches within design, procurement, manufacturing and project management.

Few companies have all of the necessary expertise in house and in any case, because demands for specific skills are usually sporadic, it does not make sense to bring such expertise onto the payroll.

Get in touch

Related Insights

We discuss the cost and infrastructure considerations of switching to an all-electric fleet of off-highway vehicles.

EV makers in the UK and Europe are warning that Zero Emission Mandates are simply not doable and subdued levels of demand could force them to close factories. Should the industry embrace Chinese capability before it’s too late?

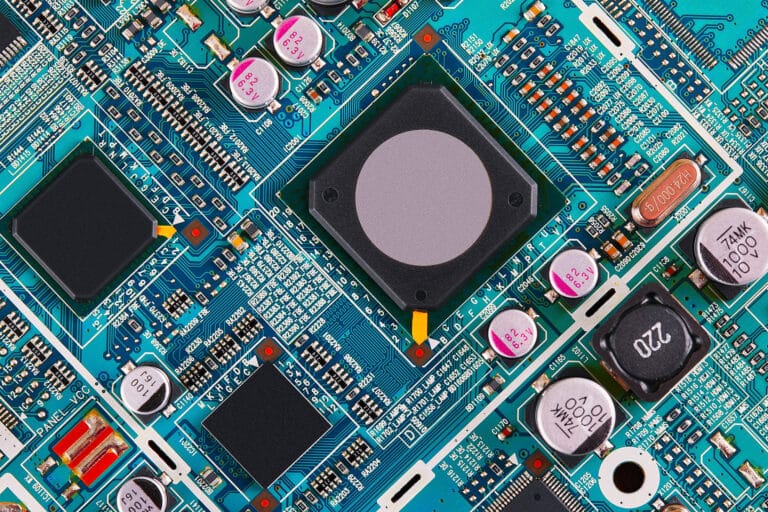

In our latest report we examine the impact of power electronics and the importance of inverters in EV manufacturing.

Subscribe to our newsletter